College football's biggest losers are thriving in 2024. Thank the transfer portal.

The transfer portal has allowed college football teams to build solid rosters overnight. Even teams like Indiana and Vanderbilt.

2024 has been a great college football season—big upsets, fun storylines, week after week with great games. And it might be the best season for Teams That Historically Suck ever.

Here’s a list of the worst power conference programs from 2000 to 2023. And then here’s how they’re doing in 2024 in bold and italics.

Kansas, 95-192 (.331) 2024: Look, the list is getting off to a bad start here. But read on.

Vanderbilt, 96-191 (.334): 2024: 5-3, beat top-ranked Alabama

Duke, 104-188 (.356) 2024: 6-2, lost by one point to 7-1 SMU

Indiana, 103-181 (.362) 2024: 8-0!!!!!!! HAS NOT EVEN TRAILED IN A GAME YET! HOT DAMN!!!!!!!!

Illinois, 111-176 (.386) 2024: 6-2

Colorado, 115-176 (.395) 2024: 6-2, has a very famous coach

Syracuse, 123-169 (.421) 2024: 6-2

SMU, 124-169 (.423): 2024: 7-1, only loss to undefeated BYU

Seven of these eight suckers have winning records, and Kansas’ awful season is the result of a tragicomical series of close losses. One of these teams is widely expected to make the College Football Playoff, and another is in the running. If I pushed the list to the 11 worst teams of the century instead of 8, I could’ve included 8-0 Iowa State as well.

There are a few reasons why these teams have all shifted fortunes so dramatically—but broadly, there’s one big one: Players are allowed to leave one school and play for another the very next year.

The transfer portal—just a website and app operated by the NCAA, although they gave it a really cool-sounding name—officially launched in 2018. Things really ramped up in 2021 when NIL payments became legal and the NCAA axed the rule making players sit out a year upon transferring. As of this season, players can officially transfer as many times as they want with no repercussions.

The portal is often cited as one of the big factors in college football “getting worse.” (We love to say the sport is “getting worse” and then we watch the games every week and they’re awesome.) The ability for players to switch teams as often as they want has undoubtedly disrupted the culture of college football, and the culture of college football is a big part of why fans care about college sports when we could just watch the pros.

But part of the culture of college football was “some teams suck every single year forever and can’t really do anything about it.” And in 2024, that’s not the case anymore.

(Sorry to the SEC Network’s Alyssa Lang—nobody deserves to be cropped off at the wrist.)

Indiana, the losingest program of all time, swapped in a team that doesn’t lose.

The Hoosiers have lost 713 games in program history, the most of all time. (They took the Biggest Loser crown from Northwestern in 2012—Go Cats.)

Zero of those 713 losses have come this season, as Indiana is 8-0 under new head coach Curt Cignetti. ESPN gives them a 69 percent chance of making the College Football Playoff at this point.

Indiana was still losing badly until last year, going 9-27 over the last three seasons. But Cignetti was able to swap out a bad team for a good one overnight. He brought in 31 transfers, including 14 from James Madison, where he went 11-1 last year and 52-9 overall.

Cignetti packed his incredibly successful JMU squad into a U-Haul and brought them to Bloomington. Indiana’s leading receiver, Elijah Surratt? He’s a JMU transfer. The team’s leader in sacks, Mikail Kamara? Also a JMU transfer. The team’s leader in interceptions, D’Angelo Ponds? Surprise! JMU transfer. The running back with eight touchdowns, Ty Son Lawton? You’re not gonna believe this: JMU transfer. So many people on this team gave up the title of “Duke” you’d think the British press disapproved of their marriages.

And 17 players transferred in from other schools, including star QB Kurtis Rourke from Ohio. He’s good.

Vanderbilt, the hopeless nerds of the SEC, got a star QB and pulled the upset of the century.

Vandy is the school stuck in a league where they didn’t belong. Since 1932, they’ve been blessed and cursed to be in the powerhouse-packed SEC because their administrators didn’t realize the papers they were signing would condemn decades of high GPA athletes to brutal ass-kickings by future first-round draft picks. The ‘Dores regularly go winless in league play.

And then Vandy beat top-ranked Alabama.

Vandy. Beat. Bama. Still feels good to say out loud. Let’s watch it again.

It’s a win which will be remembered for decades, with students walking the goalposts three miles, down Lower Broad, and dumping them into the river. The Dores are 5-3 overall and came close-ish to beating Texas Saturday. I think they can get to four wins in conference, which is a Vandy dream season.

The Commodores had been unwilling to import transfers until recently, taking just three in the 2023 class, but took 22 this past year. The star is obviously Diego Pavia, who was already a niche college football legend for achieving stunning success at New Mexico State. Before he helped Vandy beat Bama, he helped NMSU beat Auburn—less headline-y, but still an incredible upset. In 2024, NMSU coach Jerry Kill retired, but took a behind-the-scenes advising job at Vanderbilt, and the Aggies’ offensive coordinator, Tim Beck, took the same job at Vanderbilt. Pavia went with them. His top target, Eli Stowers, also came from NMSU after starting his career as a 4-star QB prospect at Texas A&M.

The list of transfer turnarounds goes on and on.

SMU hadn’t been bad in recent years, but wouldn’t have been able to level up and contend for a conference title immediately in the ACC if not for a roster already built out of power conference players. 18 of their 22 starters began their careers somewhere else. Their offensive line is all transfers—players from Oklahoma, Texas, Texas A&M, Miami, and Auburn.

Colorado has gone from 1-11 to 6-2 in just two years with up-and-coming Deion Sanders, the first-ever head coach hired directly from an HBCU to a power conference head coaching job. Sanders went 23-3 in his final two seasons at Jackson State while recruiting well above the usual HBCU level, and was able to import many of those players at Colorado. (Haha, just wanted to see what it would be like to write about this team like they were a normal program for two sentences.) Coach Prime essentially told the team’s existing players to scram while bringing in 52 (fifty-two!!!!) transfers in 2023 and 43 (forty-three!!!!) this past year. The Buffs went 4-8 in Year 1—the most mocked 400% win increase ever—and are in the running for the Big 12 title in Year 2.

I could keep going! I wrote out a section about Syracuse being 6-2 with Kyle McCord, last year’s starting QB at Ohio State, but he threw five interceptions last week and I deleted it.

It felt like that changes to transfer policy would be a rich-get-richer situation.

Over the last decade, many worried that the cascade of changes to NCAA transfer policy along with broader acceptance of transferring would tilt the already slanted playing field of college sports even steeper for the big boys. Can’t they just pay the best players now?

The most prominent transfers of the 2010s were back-to-back-to-back Heisman winners Baker Mayfield, Kyler Murray, and Joe Burrow, who boosted big-time programs. There was particularly big fallout when Jordan Addison, who won the Biletnikoff Trophy at Pitt, took big NIL money to play for USC instead. “These types of moves were inevitable with the transfer and NIL changes,” wrote ESPN’s Kyle Bonagura. “Ultimately, the current state of things will make it tougher for smaller schools to compete.”

At a Congressional hearing about NIL—side note, why were there so many Congressional hearings about NIL—Texas representative Beth Van Duyne asked “how difficult will (it be for) smaller schools be able to stay competitive when the larger schools can afford to pay athletes more?” You can find similar concerns on any college football message board, each of which is like a mini version of Congress.

But data shows the Transfer Portal boosts lower-status teams more than blue bloods.

In May, a team at Indiana University-Indianapolis’ Sports Innovation Institute produced a great study examining the effects of the transfer portal in football and men’s basketball on the 2023-24 college sports seasons. (Presumably, they really wanted to know what Coach Cig was gonna cook up for the Hoosiers.) They sorted programs in the two sports into tiers—I would’ve loved to be in the meeting where a bunch of data science grad students decided which college football teams belonged in Tier 1—tracked the raw number of inbound and outbound transfers, then analyzed the impacts of those transfers on team success and player statistics.

Here are the three most interesting things they found, summarized:

Players tend to migrate down rather than up. 9.1 percent of outbound transfers were players leaving “tier 1” football programs, while only 5.6 percent of inbound transfers joined those programs. 444 players left Power 5 football programs, while only 316 transferred in, a net gain of 138 players for non-power teams.

Checks out, right? Top-tier programs recruit pretty well and don’t need to add through the portal. They actually recruit so well that they end up with too many talented players, many of which leave.

Players who transfer down have bigger impacts than players who transfer up. The study found wide receivers who transferred down averaged 132 more yards than they did the previous season, while wide receivers who transferred up averaged 167 yards less. Basketball players transferring down played 6.7 more minutes per game and 3.4 more points per game, while players transferring up saw 4.0 fewer minutes per game and 2.1 fewer points per game.

Checks out, right? Players headed down might be the best player in their new program, while players headed up are joining crowded squads filled with talent. So the study found more players moving down than up, and that players moving down had bigger impacts than players moving up. That’s a huge increase in talent and production for lower-tier schools.

Teams which import a lot of transfers have a great chance of improving quickly. Teams with rosters comprised of 20 percent new transfers (or more) averaged 1.06 extra wins per year than they had the previous years.

CHECKS OUT, RIGHT?!?!? If you’re recruiting dozens of transfers, you probably didn’t have a good team last year. But those players can instantly help you start winning more games.

(It’s also worth noting that this study showing players transferring “down” does not even really capture situations like Indiana and Vandy importing the best parts of successful rosters at James Madison and New Mexico State.)

The old system was incredibly beneficial for the biggest schools.

Let’s do a one-school case study on the shifting ability to retain talent in college football. (Sorry I can’t do a bigger study like the IU-Indiana one—I have no idea what computer stuff people do to make them hjappen. You’re saying you did this in “R?” Am I hearing you correctly? “R?” Like, the letter “R?” ) Let’s look at Alabama in The Olden Days—10 long, long years ago, before any Tiks had ever Tokked—and now.

Alabama had the top recruiting class in the country each year from 2012 to 2014, landing 16 5-star recruits and 43 4-star recruits. All 16 of those 5-stars stayed at Alabama for their entire careers, and only nine of the 43 4-stars left. (And some of those nine left because they were arrested and dismissed from the team and needed to find someplace else to play.) So in three years, Bama got 49 blue chip prospects who spent their whole career with the Tide. That’s more than they needed! You can’t play 49 guys! Some of those guys rode the bench, but they all stayed at Bama.

Alabama almost pulled off the same back-to-back-to-back best recruiting feat from 2019 to 2021, when they had the best class twice and second-best in 2020. They got 14 5-stars and 59 4-stars—but this time around, they only kept nine of those 5-stars, and lost over half of those 4-stars—34 out of 59. (I was worried this sample would be skewed due to Nick Saban’s retirement—but only one of those 39 blue chip transfers came after Saban’s late departure in January. It might actually be an undercount, since some of the remaining blue chippers are still in school and have yet to transfer.

This tells a simple story. Ten years ago, Alabama would go to the top recruits in the country and say “come to Alabama, you’ll win national championships and play in the NFL,” and they’d say yes. Then half would end up stuck on the bench, but they stayed anyway. The top high school players still go to Alabama, just like they did a decade ago—but now they might finish their careers as starters at SMU and Colorado instead of staying blue blood backups.

College football will always be a sport of haves and have-nots. But there’s more hope for the losers now.

The powers in college football did not keep players from transferring because they wanted to make sure everybody had a shot. They did it because restricting player movement made it easier to control players. That conveniently enforced an uneven status quo where the best programs got the best players and kept them.

As it turns out, those restrictions were more-or-less illegal, since players remain unpaid and not legally considered employees, which is why the NCAA actually had to change them. Thank you to the United States Department of Justice for making Indiana good at football. (More like the United States Department of Justice Ellison, am I right?) (He’s Indiana’s running back.) (He transferred from Wake.) (Sorry, this joke wasn’t that good and required a lot of explanation.)

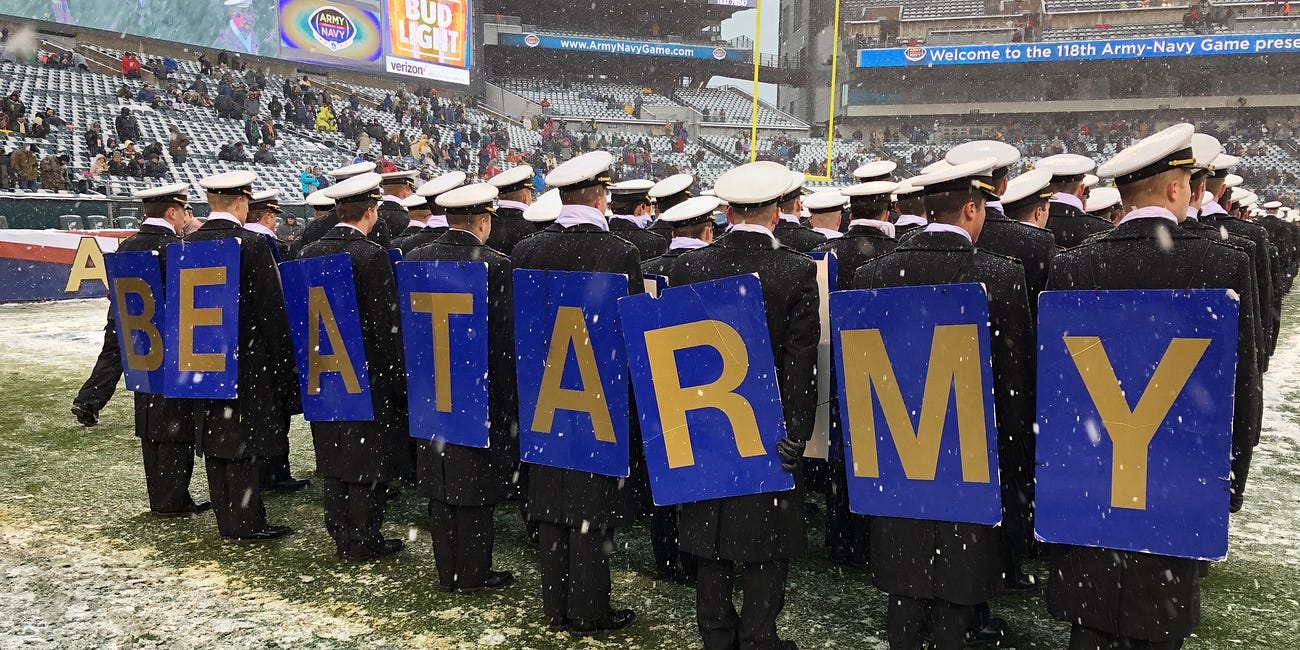

Look, I get it. Just a couple weeks ago I was getting all romantic about Army and Navy for thriving without transfers.

Army is undefeated. Navy is undefeated. What happens next?

This is the first time anybody has been able to read about Army and Navy being good at the same time on the internet.

Part of college football fandom is that you get to watch a player develop from an unready freshman to a confident contributor over four-to-five years at your favorite university. Just like you went from being an innocent wide-eyed 18-year old to something approaching adulthood over a stint at the same school. Now, half the team swaps out by the time they graduate, and the few guys who stay get bumped down the depth chart by transfers. We lost something with the portal.

But I’ll trade that romanticism for a sport that doesn’t illegally restrict unpaid players. Somehow, we got that and a sport friendlier to underdogs and tougher for the blue bloods.

Most of the coming changes to college football will not make life easier for the little guys. So let’s celebrate this moment when the right thing to do turned out to be the fun thing to do. It’s a win for the ages, just like Vandy-Bama. Let’s dump these damn goalposts in the river.

It's interesting to see the transfer up/down stats because it feels like the dynamics here could be really different sport to sport! Thinking about softball where OU has used the transfer portal *heavily* during their 4 straight years of championships, though they have also had a decent number of transfers out. But maybe it's just easy to get an impression from the biggest stories that doesn't capture the full dynamics of what's happening.

This is a good-read. MAYBE the transfer portal is the answer to evening the playing field and conference consolidation in college football. If teams like Indiana thrive, then the Big Ten powerhouses will want to find ways to expand the CFP and get more at-large spots in play…which would help non power 4 programs get in on the fun.

Player empowerment having a positive effect? Who would’ve thought!